A December 9 article on the recent Newton School Committee decision to align NPS’s graduation requirement with state guidance referenced an interim report from the Chair of the Massachusetts K-12 Graduation Council, Secretary of Education Patrick Tutwiler, that offered an important insight: “Based on information issued by the state last week, it’s unclear how, or if, the vast majority of NPS students will experience any meaningful changes in their high school experience.” This is correct, but not for the reasons readers might think.

First, although the report’s cover page implies that it is authored by the Graduation Council, Secretary Tutwiler and DESE Commissioner Pedro Martinez determined all the report’s recommendations without a vote by the 30 other Council appointees. The report was not written by the council.

The substance of the report fails to offer meaningful change because it ignores basic principles of curriculum design that any first-year teacher knows. Referred to as “backward design,” the process first establishes goals and outcomes, then creates assessments to measure attainment of those goals, and lastly plans educational experiences aligned with both. This ensures a coherent, accountable curriculum. However, the Secretary skipped and rearranged these steps (see page 7 of the report). Instead, coursework drives the report’s entire process in its assumption that MassCore will be required of all schools. Therefore, content acquisition – not skills or habits of mind – is its real goal, which runs counter to both input from commission members and input from its “listening sessions.” The “Council’s” report doubles-down on an outmoded, alienating approach to learning, ignoring the lack of student engagement that underlies the stilted academic progress currently plaguing American education. The Secretary sits foursquare behind a 19th Century solution to a 21st Century challenge.

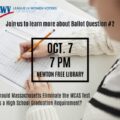

But why is this happening? I submit that mandating content – to be assessed via standardized End-of-Course assessments – provides cover for reinstituting MCAS testing in a more streamlined form. This is a pedagogical step backwards that undermines the clear majority who voted against high-stakes testing in 2024’s Ballot Question #2. End-of-course testing will continue to incentivize instructional strategies that center rote learning of siloed (and ultimately unretained) content over deeper, engaging, integrative, authentic learning experiences. It will perpetuate the alienation and transactional view of school that I have seen students have expressed for a very long time, and de-value teachers through the use of so-called “high quality instructional materials” that benefit their publishers far more than students. This approach, as proven by those selfsame MCAS scores, has done little to close learning gaps or keep up with changing academic needs. Yet the Secretary would turn accepted curriculum design on its head to keep it in place.

The irony is that the design process could have started with the report’s “Vision of a Graduate” (see p. 11). Similar in many respects to NPS’s “Portrait of a Learner,” it sets out comparatively rich goals, developed with community feedback drawn from the Council’s listening sessions, and overwhelmingly aligns with input garnered from a parallel process conducted by Citizens for Public Schools (CPS). Both conclude that parents, students, educators, and community members want emphasis on critical thinking, problem-solving, and graduates to have the ability to collaborate and communicate in their post-graduation lives. The problem is that complex skills don’t lend themselves to standardized testing.

It might be easier to test content recall than it is to assess the more complex skills that the Vision of a Graduate embodies, but we need to teach and measure those skills. True, it is difficult to capture attainment of those skills in a test result, but those who suggest that the current MCAS scores are, ipso-facto, “objective” kid themselves. Standardization is categorically not the same thing as objectivity: If I decide everyone should wear size-six shoes, that sets a standard. Everyone is held to it, and I can even compare those who meet the standard with those that don’t, but that doesn’t mean my choice of size-six was objective. Standardization and objectivity are often incorrectly conflated.

The good news is that there are fair and comparable ways to assess complex skills, and we should look to develop them. The Massachusetts Consortium for Innovative Educational Assessment is a good place to begin that process. We need assessments that align with our stated goals. We need to treat students more like people and less like human capital, and that means rejecting the back-to-the-future pedagogy and cynical dismissal of the will of the voters that characterize the Secretary’s report. The Newton School Committee was right to reject a return to using MCAS as a graduation requirement. It should do the same with this attempt to usher-in MCAS 3.0 through a side-door, and also lobby the Legislature and Governor to replace the Secretary’s proposal with something more thoughtful, academically meaningful, and respectful of the democratic process.

Jim Murphy is a career educator with nearly 40 years of experience in multiple Massachusetts school districts. He is a Newton Highlands resident and a recent candidate for Newton School Committee.