In a time of nationwide turmoil in the 1960s and 1970s, the Newton Public Schools (NPS) took a lot in stride: a homemade bomb exploding, major changes in school governance, and the beginning of significant cultural wars.

On a Friday morning in November of 1968, a homemade bomb exploded in the original Newton High School. “The blast ripped a lock from a heavy oak door and lifted an eight-foot locker six feet into the air.” Fortunately, no one was in the hallway. The school was evacuated, aired out, and, after 15 minutes, the students returned to class. According to Headmaster Richard Mecham: “There hasn’t been a bomb threat for well over a week. You never receive a warning on the real thing.” A 15-year old boy was charged with “being a juvenile delinquent” and suspended. He “denied the charges emphatically.”

Newton South High School, opened in 1960, was not immune to trouble. Police bearing nightsticks disbursed gangs of boys and girls ready to rumble in the parking lot more than once. Students fought in the cafeteria, taunting each other with racial slurs and ending up in the hospital. Vandalism was a problem in elementary and junior high schools, as well as on school buses. The problem was not unique to Newton. Rates of violent and property crimes in Massachusetts more than doubled between 1966 and 1971 and continued to rise through the 1990s. NPS high schools were still considered among the best high schools in the nation.

A new high school for the North Side

On August 12, 1968, the Board of Aldermen approved a new North High School at a maximum cost of $15.4 million. There was no public meeting about that because building a school was not considered controversial. It was “just something that had to be done,” said Alderman Flaschner, “… we shouldn’t open it up for a political rally.” The State Board of Education approved the project in May of 1969 without a site plan or estimated costs for site development. According to its Annual Report, “Newton refused to submit plans for site development.”

When the high school faculty saw the school plans, they were not pleased, especially with the windowless rooms. Mayor Basbas told the faculty that they should have attended the planning sessions the previous summer. The City had already spent $400,000 on architects Perry, Dean, and Stewart. A redesign and delay would endanger the project. A year earlier, during the planning of a new Bigelow school, City officials had explained that current architectural theory “rules out large windows and replaces them with artificial light, which is more constant than natural light,” and air conditioning.

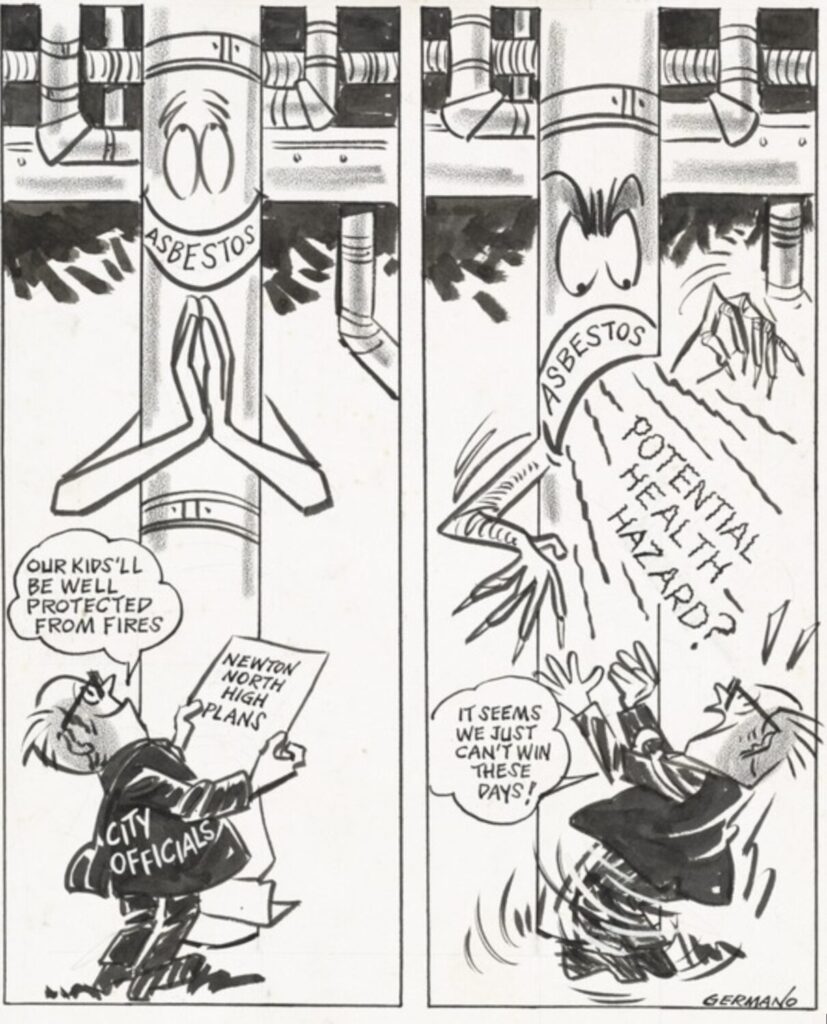

Newton North High School opened in 1971. By 1975, the building was winning national accolades for its skillful design, and the City was suing both the contractor and the architect “for alleged defects in construction.” Parents had begun protesting about a white powder falling from the ceiling. They were told testing found “Asbestos not serious in the air at North.”

High school protests were not limited to the new building. When anti-war activist, historian, and Newton resident Howard Zinn was selected by the seniors of Newton North High School in 1970 to deliver the graduation speech, Mayor Barbas boycotted the event, and 40 to 50 parents walked out. The remaining attendees gave Mr. Zinn a standing ovation. NPS estimated that half the high school class attended a May 4, 1971, rally protesting the Vietnam War on the Boston Common.

City Charter reform

“When we started having open meetings … everybody who came, said ‘that awful, horrible school, we don’t know why we have that school and why it was allowed to be built that way.’ It was flabbergasting, frankly. So we put into the Charter a provision about how to select an architect and the Design Review Committee.” Florence Rubin, Chair of the Charter Review Committee

On November 2, 1971, Newton voters approved a new City Charter. The new charter added procedures for citizen referenda, special elections to fill vacancies (instead of the School Committee, Board of Aldermen, or Mayor appointing new members), and preliminary elections to ensure that the winner in the general election received a majority vote. A Designer Selection Committee, a Design Review Committee, and a process for public hearings were also included to prevent another building “everybody hated.” The School Committee was made solely responsible for the maintenance and repair of school buildings (previously shared with the City), and “School Committee members were limited to four consecutive 2-year terms so that fresh viewpoints will be assured.” School Committee members remained unpaid.

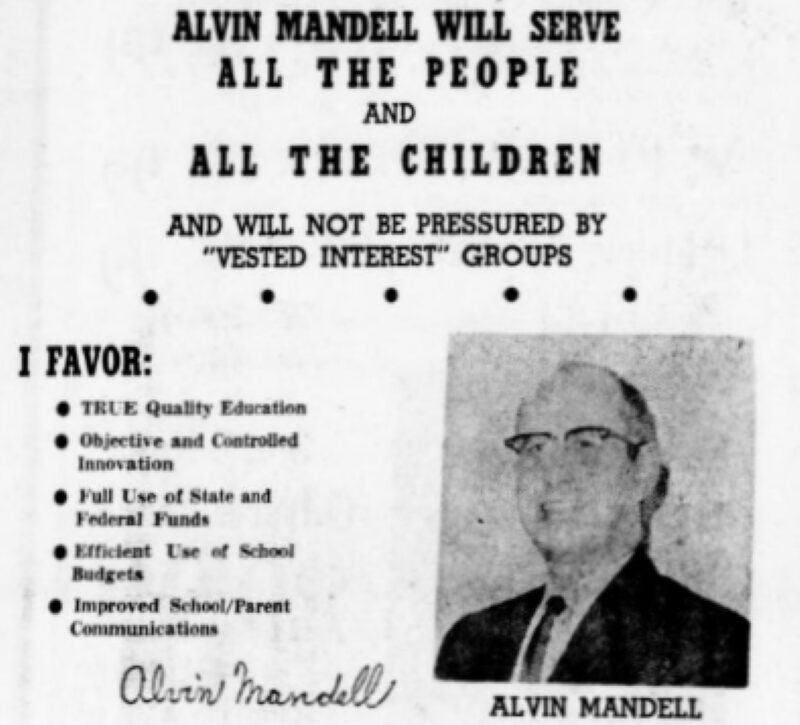

School Committee member Al Mandell was on the Charter Review Committee. He and Alderwoman Adelaide Ball wrote the minority (dissenting) report. They opposed the Commission’s recommended limit of 4% of the previous year’s school budget for maintenance and repair. They thought it was too high and would lead to wanton spending. They wanted the School Committee elections changed from citywide to ward-based, “to provide for better minority representation,” and felt that low-turnout special elections would be a waste of money. They stated that term limits only for School Committee members were “discriminatory.” It was rumored and denied that the term limits were instituted to “get rid of Al Mandell.”

In 1973, Mandell was the top vote-getter on the School Committee (11,670 votes). He ran unopposed and was endorsed by the Newton Graphic: “Alvin Mandell appears to be the outstanding member of the committee. He knows exactly what the School Committee function really is.”

The MACOS cultural war

In January of 1970, Time Magazine wrote about an experimental 5th-grade social studies program in Newton called A Man: A Course of Study (MACOS). MACOS was first piloted at Underwood during the summers of 1965, 1966, and 1967. NPS staff, from teachers to Superintendent Brown, were part of a large team of artists and academics that designed the curriculum under the direction of Harvard University psychologist Jerome Bruner. “MACOS sought to revamp social studies education by addressing big questions about humans as a species and as social animals,” using anthropological methods and inquiry-based learning. MACOS was built on Bruner’s belief that “all cultures are created equal.”

The fifth-grade curriculum was funded by the National Science Foundation (NSF) because no commercial publisher would produce it. It cost four times as much as a standard curriculum. Its materials included dozens of student booklets, wall maps, games, a paper seal to be cut up and shared according to Inuit rituals governing who was entitled to which part of the animal, and 8 half-hour movies that recreated traditional Netsilik Inuit life. Dialogue was only in Natsilingmiutut to immerse the students in the experience. “Instead of telling students how people in other cultures behave and why, the films permitted children to figure things out for themselves through direct observation.” (Wolcott)

MACOS went nationwide in September 1969 and was followed by alarming headlines such as “Is your 10-year-old watching ‘X-rated’ films at school?” (Dow), Congressional hearings, three federal investigations, and the end of NSF K-12 curriculum grants.

The program was attacked on two grounds. First, it was seen as a dangerous step toward a national curriculum that threatened local educational control. Second, its cultural relativism was considered amoral. “The critics charge that in studying the Eskimos, children are receiving positive teaching about killing the elderly and female infants; wife swapping and child marriage; communal living; witchcraft and the occult, and cannibalism.” “A broad conservative organizing effort, whose effects can still be felt today, eventually ended not only MACOS, but the very viability of school curriculum reform projects on the national level.”

A 1977 Federal longitudinal study found that MACOS students enjoyed their year of social studies more than non-MACOS students, and that both groups ended the year with similar cultural beliefs. “Two MACOS students, out of over two hundred interviewed, mentioned that the act of abandoning the old woman on the ice was desirable in the sense of being necessary for group survival. Most students who mentioned the event at all thought some other solution should have been found. …Many students in both groups, MACOS and non-MACOS, when mentioning a custom that was different from ours, but not seemingly cruel or unfair, would add statements to the effect that “they have their ways, we have ours.”

Next: Part 12 – Special Ed, Unfunded Mandates, and School Closures

Bibliography

Dow, Peter B. Schoolhouse Politics: Lessons from the Sputnik Era. Harvard University Press, 1991.

Garboden, Clif. “Would You Pay $2000 a Year for this Child’s Education? If you lived in Newton, you would.” The Boston Phoenix: Suburbia, February 4, 1975, pp. 14-20.

Newton Public Schools, and Barbara Harrison. “Unique Program at Davis.” Inside View, vol. 2, no. 1, 1967, p. 5.

Wolcott, Harry F. “The Middlemen of MACOS.” Anthropology & Education Quarterly, vol. 38, no. 2, 2007, pp. 195-206. JStor. Accessed 16 February 2026.