As I write this, it’s been eight weeks since the world lost Setti Warren at the appallingly unfair age of 55. To me, he was a friend, mentor, boss, and big brother. Right until the day he passed, I spoke with Setti just about every day for the 20 years that I knew him, sometimes a dozen or more calls over the course of a few hours. The idea that he isn’t here, that my phone won’t be lighting up with his name on it anymore, is nearly impossible to comprehend.

I probably spoke with Setti on the phone 50,000-60,000 times over the years, to say nothing of the countless texts and immeasurable hours spent together. Topics usually included the viability of some candidate running for some office; something that somebody did or said at Harvard, where we worked together for several years; the latest developments in Newton; whatever the Red Sox did last night; and a very healthy dose of “remember that time…” So, over the last few months, my mind has taken me back to about a million moments and memories.

Setti gives an intern a chance

My memory brought me back to the start, a September morning in 2005 when I paced nervously up and down Cambridge Street at Bowdoin Square in downtown Boston. It was my first day as a college intern in the Boston office of United States Senator John Kerry, but rather than bounce eagerly up the elevator and into the office, I fretted anxiously about whether to even go inside, or just go home and ditch the opportunity all together. I was terrified because, more than simply my first day as an intern, it was my first time ever doing anything in a professional office environment.

Back then, I was a mediocre student at UMass Boston and a budding political junkie. I had fumbled my way through high school at Newton North without so much as a passing concern for minor details like homework or classes – eventually dropping out part way through my junior year. So when I finally got my act together, after finishing high school late and enrolling in college after several directionless years of working odd jobs, the many political and government internships I applied for weren’t exactly competing for my services. But with a little persistence, and probably a great deal of luck, I won a spot in the cohort of fall 2005 interns in Senator Kerry’s office, where Setti was a senior staffer.

After a few weeks of answering the phones and printing canned responses to constituents’ letters, I was surprised one day to see Setti – whom I had met only briefly – emerge from his office saying, “Hey, can you help me with something?” He was planning an enormous conference for small businesses from across Massachusetts, and he needed help with the voluminous outreach, planning, and execution. It was a seemingly benign moment that wound up completely changing the trajectory of my life. In hindsight, it was like the coach calling me from the end of the bench and putting me in the game. As Doc “Moonlight” Graham’s character in Field of Dreams said, “I jumped up like I was sittin’ on a spring.”

We quickly hit it off, discovering we were both from Newton and had a shared appreciation for 1980’s Boston sports references, and repeatedly quoting the same few lines from popular mafia movies. We had attended the same high school, ten years apart and with polar opposite experiences – him the Class President four years straight, me an invisible truant who barely got out of there with a diploma. He let me stay in the Senator’s office for a second semester, an unusual practice at the time, and would later bring me back in for occasional help when there were big projects or major events. I was fairly certain that no other intern in the office was fielding calls from their boss at 11:00 at night, or getting emails throughout the weekend asking for their opinion on the third, fifth, eighth, and fourteenth drafts of a speech. I didn’t care. Who needed a life when you could be a part of something like this? It was completely worth it, then and now.

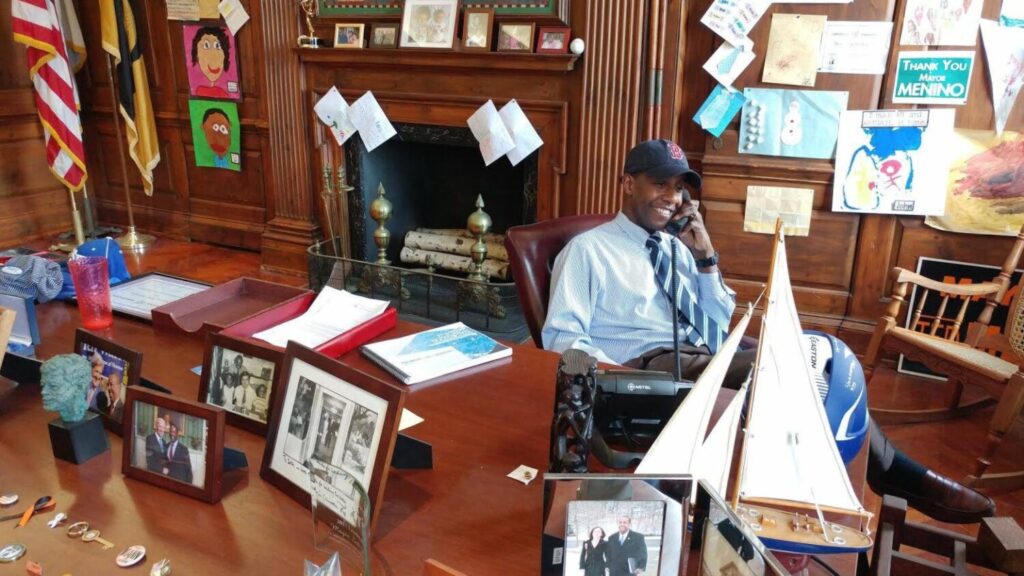

Mayor of Newton

We stayed in touch, and when he decided to run for mayor of our hometown, I poured all my time and all my energy into it. Working on his campaign for Mayor of Newton in 2008 and 2009 had the distinct feel of a startup that was destined for great things. We had no name recognition, less funding than our opponents, and we were strangers to most of the political establishment in the city. But we had an absolute certainty that it would all work out – that the young, cool candidate with swagger had a plan and was the right person at the right time. Knock on enough doors, meet enough people, and eventually others will see it too. Incredibly, it actually worked. And when he asked me to join him in the Mayor’s Office, I said “yes” without even thinking. There was nothing to think about.

Those early days in the Mayor’s Office feel like a blur. In 44 years of life, I have truly never seen anyone work harder at anything than he did at being Newton’s Mayor. Keeping up with him was impossible, and all I could do was try. The volumes of ideas he had, of meetings he held, of questions he asked, of people he saw and places he went were simply staggering. And if he asked you to take care of something, he wanted it done yesterday. Sometimes he would ask me to place a call to someone about something, and after several more minutes of talking through various other updates and questions, he would ask if I had made the call yet. (“I’m still sitting here with you. How could I possibly have done it?,” I would think to myself with a smile.) He worked unbelievably hard. His expectations were high, but he set the standard for others to follow.

Expecting the unexpected

Sometimes the steps he took were surprising, even to those closest to him. During one of his first budget cycles, we had to eliminate a few positions, and union members responded by protesting outside City Hall. We could hear them loud and clear from our second-floor windows. We sat in my office listening to them chanting, and we asked ourselves what, if anything, we should do.

Finally, he asked me, “What if I just go down there and talk to them?” It seemed like the opposite approach to the one most people might have taken, and I wasn’t sure what he expected to gain. But down he went, and I followed right behind. The protestors were furious at him. He cut their jobs, and, they argued, their livelihood. But he stood in front of them, looked them in the eye, and listened to them. Then he told them how sometimes his job was to make difficult decisions that were in the best interest of the city as a whole, and this was one of those times. To a person, each one of them came over, shook his hand, and thanked him for his time. There were no cameras rolling, it was just the right thing to do. “Talk to everyone,” he would say.

Everything all at once

Sometimes doing his job meant having an almost superhuman ability to compartmentalize, or even just to stay awake. One Sunday in March of 2010, just a few months into the job, Newton experienced some of its worst rain and flooding in a century, resulting in cars along Quinobequin Road floating in their driveways and basements severely flooded throughout the city. The very same day, Setti’s father suffered a massive stroke, which would claim his life just a few weeks later. The next day, Setti arrived at the office exhausted, having been awake at the hospital all night, wearing corduroys and a ragged old sweatshirt. With eyes red and barely standing upright, he convened a meeting of all the key department heads to get updates on the flood damage and the City’s response so far, and he directed various communications to residents and businesses. The message to staff was clear: the work of government and our responsibility toward our residents never stops, no matter what.

Fun

But for all his focus and hard work, he always made time to have fun. Charles River Chamber of Commerce President Greg Reibman was right-on when he said in a recent message, “Possibly the only thing better than Setti Warren’s handshake was his laugh.” In between the trials and tribulations (and in between just about every single meeting and phone call) we had a lot of laughs. So. Many. Laughs. The man could find humor in nearly anything, and he delighted in the short break that a good laugh would give him. There are so many moments – some of which recurred countless times in ever predictable fashion – that I will always cherish.

He would crack himself up by referring to the most minor of tasks in grandiose political or logistical terminology. When getting ready to leave City Hall for the night (or sometimes just to go down the hall) he would say “Let’s mobilize and prepare for departure,” harkening back to his days in the Clinton White House when “departure” involved weeks of planning, hundreds of staff people, and the coordination of countless government agencies, municipalities, airport staff, EMTs, and on and on. Most days in the Mayor’s Office, “departure” meant walking down a flight of stairs and getting into my beat up old pickup truck.

A staple of our days together were the endless hours of me sitting in his office rattling off various updates and questions from whatever had come up so far that day. Sports metaphors laced his speech. If he wanted to move quickly, he would have a good laugh over telling me that we were in a “no-huddle offense.” When I would inevitably get to an item that required a greater degree of thought and consideration, he would elaborately declare a “timeout on the field” or tell me that “Coach Belichick might need to throw down the challenge flag on that one.” This joke, if you want to call it that, ran strong for literally 20 years.

Left “in charge”

Sometimes the circumstances that unfolded were so absurd, you almost had no choice but to laugh. In those first few years, Setti practically lived in the Mayor’s Office. His days were an endless stream of meetings and phone calls, with him occasionally popping out for a quick event somewhere in Newton before returning to the grind. But one Friday afternoon in 2010, he was scheduled to attend a meeting at the Massachusetts Department of Transportation offices in Boston. He stuck his head into my office briefly before heading out. “I’ll be back in a few hours, you good? Steer the ship, brother! Steer it!!” Brimming with pride, I was ready. It was like your parents leaving you home alone and in charge for the first time.

All went smoothly for nearly ten full minutes, at which point someone from the mailroom brought to my attention a letter addressed to the Mayor with what seemed like a small, jagged object inside and no return address. They felt that it looked suspicious, and I agreed. Not wanting to take any chances, I contacted the Newton Police, and an officer quickly arrived. The officer shared our concern, and soon the Fire Department and State Police were brought in. When the State Police Bomb Squad was called, we were asked to evacuate the Mayor’s Office. Then, the entire building was ordered to clear out. Before long, the Newton Free Library was emptied too. In a matter of minutes, seemingly every reporter and television station with a police scanner was calling me, looking for information.

Barely 30 minutes after leaving, the Mayor was back, having skipped his meeting in Boston. He returned to City Hall to find Homer Street closed; both City Hall and the Library evacuated with hundreds of people having streamed onto the street and sidewalks; nearly every media truck in Greater Boston camped out with cameras rolling; and an enormous contingent of Newton Police, Newton Fire, State Police, Sheriff’s Office, and Bomb Squad vehicles surrounding the building. My first time being left “in charge” had quickly ended in a calamity beyond anything I could have imagined. The icing on the cake was when we were informed that the “suspicious package” was simply an envelope containing a broken piece of a plastic city trash barrel, and a letter from an upset resident complaining that the barrels break too easily.

Dealing with difficult times

For all the good times and good humor, there were plenty of heartbreaking moments too. I was there to see the pain in his face when he found out (more than once) that one of our high school students had died by suicide. The same when we stood in West Newton Square on a cold March night in 2016 after Eleanor Miele and Gregory Morin were killed by a driver while doing the most innocent of things – stopping at Sweet Tomatoes to grab a pizza on the way home. And the agony in his eyes when he sat there listening to the Chief of Police describe in painstaking and graphic detail the charges being brought against one of our elementary school teachers for possessing child pornography. Setti knew that dealing with all this was exactly what he signed up for, but you could feel the heaviness in the air during those moments and so many others.

Being at his side all those years also gave me a front-row seat to the indignities that he faced as a Black Mayor, or simply as a Black man, in Newton. He was standing outside the Marriott Hotel in Auburndale one morning, waiting for the other party of a meeting to arrive, when a man in a Mercedes pulled up to the entrance and, seeing Setti standing there in a suit and tie, quite literally tossed Setti his keys and began to make his way into the hotel. Always ready with a quip and a smile, Setti simply tossed them back and said, “Thanks, but I have a car already!” Realizing his mistake (although presumably not realizing it was the Mayor, of all people) the man apologized profusely and got back in his car. Setti had a good laugh over it and gleefully shared the story with the rest of the team back at City Hall later that day, but there was no question that it bothered him. And while I would love to say that this was an isolated incident, one version or another of this occurred on a regular basis, week after week, year after year.

Family and community

Amid all the unscripted moments and unanticipated challenges, there were two throughlines that ran steadily across all the months and years, the endless twists and turns, and moments that alternated rapidly from hilarious to dead-serious and back again. The first was his ceaseless gushing and bragging about his wife and kids. They were everything to him, and he talked about them constantly. (One day in 2013 when he arrived at City Hall after dropping his daughter off for her first day of kindergarten, he was so overcome with emotion that he could barely function for the first few hours of the day.) The second was his unwavering belief in bringing people together, and ensuring that we see our common humanity in one another. In a statement to the Harvard Crimson shortly after Setti’s passing, political strategist David Axelrod said that “He practiced the politics of thoughtfulness and civility and belief that through conversation, we could build something better. The tragedy of this is we need more Setti Warrens.”

Harvard and the world need more Setti Warrens indeed, but his beloved hometown of Newton could most certainly benefit from more of him as well. The polarizing divisions in our community have begun to follow the national pattern of getting deeper and more entrenched with each passing year. I can’t tell you how many times in recent years I’ve met with someone who was surprised to hear that I am in regular contact with a notable figure in the community whose views I often disagree with. We should be the kind of community where there is nothing unusual or surprising about this. We can all have our strongly held views and convictions, but it shouldn’t prevent us from hearing each other out. Talking across differences and meeting with everyone, even those we disagree with, might not always change a lot of hearts or minds. But it allows us to maintain our humanity, and to actually live the idea that all of us who share this city together are neighbors.

This was Setti’s vision, not only for Newton, but everywhere.

A crazy idea?

In November of 2016, I was sitting with our Mayor at the long, rectangular table in his office at City Hall. We were just a few days removed from President Trump’s surprise victory over frontrunner Hillary Clinton, capping off perhaps the ugliest and most divisive presidential election in history. So when Setti told me he wanted to convene a friendly dinner composed of an equal number of Clinton and Trump voters, I shifted in my chair a few times, trying to buy a minute or so of time before responding.

“Friendly?,” I thought to myself. Good luck. Partisan divisions were at an all-time high, and the animosity between the two sides was still raw, to put it quite gently. If I tried, I doubted that I could have come up with a crazier idea. But it was hardly the first time he had proposed an outside-the-box idea, and probably not the first time that day. But after years of working with him, I knew that sometimes a thoughtful pause was the best response. I then told him that I was a little worried about how successful it would be, and wondered what success would even look like – maybe just getting through it without fists flying or insults being hurled across the table, I supposed.

But to my surprise, and surely to the surprise of some of the attendees, none of that happened. The dinner was a huge success. Three Clinton voters and three Trump voters sat together along with Setti and me, and we all talked for hours. We talked about our families, our jobs, our lives, and our worries for the country. And we talked about why we voted the way we did. A lot of ground was covered. But one thing was missing: the divisiveness and name-calling that was a hallmark of the campaign at the national level. The dinner would prove to be one of Setti’s proudest moments, because he was always adamant that if we just get people to see each other as they are, as their fellow human beings, we can build a better world, one conversation at a time.

Setti’s example for us

It’s about to be a new year, so here’s my resolution, and maybe you’ll consider doing it along with me: listen more. Hear people out. Understand where they’re coming from. Recognize that they are not inherently bad or foolish simply because they have a different perspective. Don’t be afraid to occasionally agree with the person who you usually disagree with. And resist the urge to put labels on yourself or others.

Humans are complex and so is our city. The idea that all of us can simply be boxed into “pro-this” or “anti-that” is preposterous. Setti truly believed that we were all neighbors, that we all had something we could contribute, and that everyone has some good in them. Right now and forever, I hope we can honor him by believing it too.