When METCO (the Metropolitan Council for Educational Opportunity) program began in 1966, organized opposition emerged in Brookline, Wellesley, Needham, and other neighboring suburbs, but not in Newton. METCO had “a smooth start here” without “incident or fanfare.” Instead of protesting METCO, Newton’s parents were protesting lunchtime.

Between 1940 and 1970, Boston’s African American population quadrupled, reaching over 15% of the City’s population. In Newton, it had grown from 1% to 1.2%. Boston’s public schools were de facto segregated, and the public schools with African American students had become grossly overcrowded and under-resourced. Newton resident and Davis Elementary School teacher Jonathan Kozol described this in his bestselling 1967 book: Death at an Early Age: The Destruction of the Hearts and Minds of Negro Children in the Boston Public Schools.

African American parents in Boston and their allies lobbied for better schools through petitions, marches, and Stay Out for Freedom days, during which students boycotted school and attended volunteer-run Freedom Schools that taught African American history and culture. On February 7, 1964, Newton residents Hubie and Katherine Jones arranged for over 300 white Newton children to participate in a Stay Out for Freedom Day. White students went into Boston, and African American Boston students attended Freedom Schools at Myrtle Baptist Church, the First Unitarian Society, and the Second Congregational Church in Newton

That fall, two Roxbury mothers took advantage of the district’s open enrollment policy, which allowed students to attend any Boston Public School that had space available. They organized a self-funded busing effort, Operation Exodus, through which over 400 African American children were sent to white Boston schools. Operation Exodus inspired Sylvia Kelley to approach the Newton School Committee about busing 50 African American children into Newton Public Schools. Chairman Freedman replied that the School Committee had no legal power to become involved with “the educational problems of other communities.” That changed when the State passed the Racial Imbalance Bill of 1965, which allowed school committees to “help alleviate racial isolation” (defined as any public school where over 70% of the student population is white) through voluntary cross-district enrollment.”

The Boston and Newton School Committees voted to support busing students between their communities, provided that they were not required to fund it. Newton Superintendent Charles Brown, a member of the first METCO executive board, developed a “limited project involving some 200 Boston non-white children” and wrote proposals for grants from the Federal Government and Carnegie Corporation for METCO’s initial funding. Former Newton High School principal Harold Howe II (1957-1960) had just been appointed the Federal Commissioner of Education, responsible for distributing funds from the newly passed Elementary and Secondary Education Act. He supported the use of Federal funds “to make a dent in de facto segregation.”

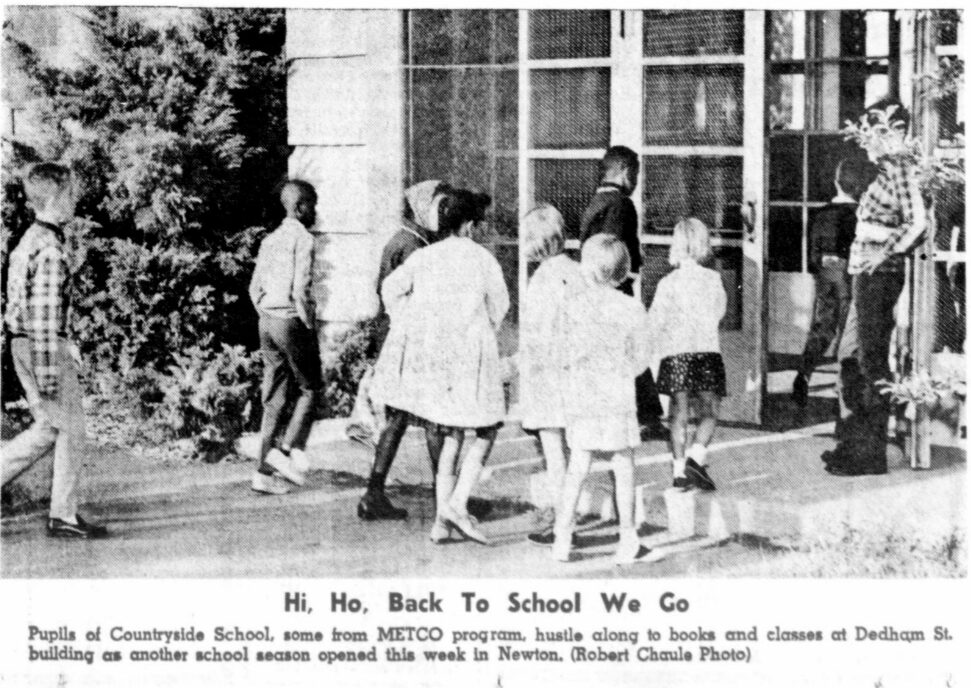

Katherine Jones became Newton’s first METCO Director. Part of her responsibility was to arrange host families to provide lunch for the Boston students during the 1.5-hour lunch break on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays. In September of 1966, the first 50 students from Boston began attending seven elementary schools in Newton.

The Lunchtime Debate

“Except as a free babysitting service for mothers, what reason is there for elementary school children to lunch in school at all?” – Letter to the Editor, Newton Graphic, January 1967

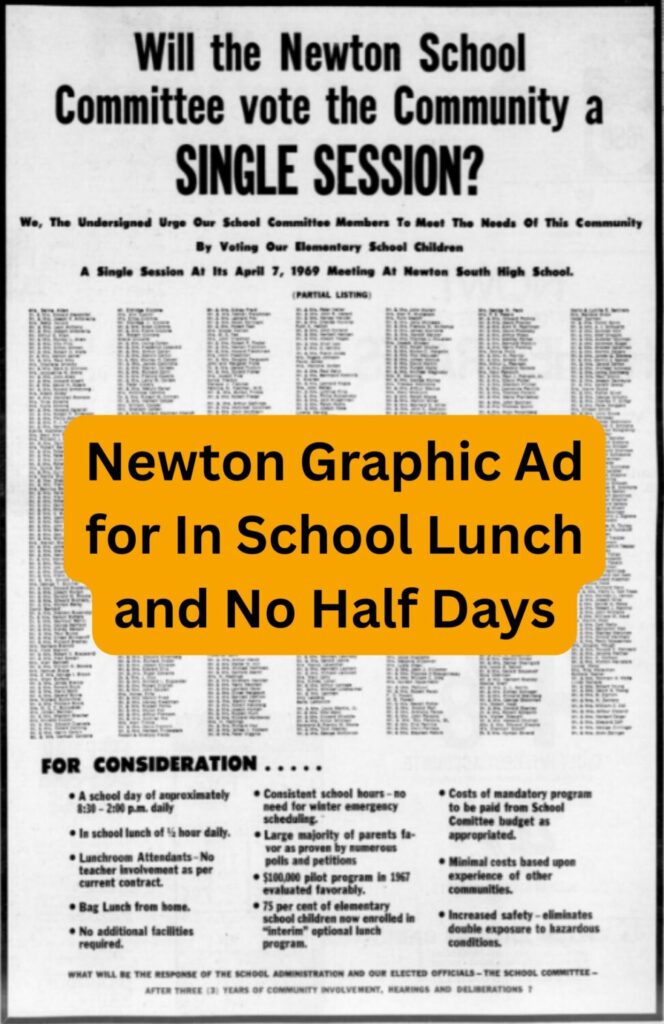

Since 1908, Newton’s elementary schools had afternoon sessions on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays, during which students were given an hour and a half to go home for lunch (noon to 1:30PM). There was no afternoon class on Tuesdays or Thursdays. “Between the fall of 1965 and the spring of 1966, a little group of pro-lunch parents managed to sneak around Newton and collect 3,000 signatures on a petition” (Hartman). Their petition called for a single session, in-school lunches, and an end to the half days. They noted that the half days violated the State Commissioner of Education’s requirement that “Elementary Schools shall operate not less than 5 hours daily, exclusive of lunch or other recess.” Along with 500 supporters, they presented their petition to the School Committee in June of 1966 and anticipated “immediate action.” The School Committee voted to study the issue. At the time, 82% of Massachusetts public school children ate lunch at school.

Those opposed to a single session included most NPS administrators and teachers. Opponents claimed that the walk home was “beneficial and healthy, home lunch was psychologically better for children, free Tuesday and Thursday afternoons were useful for extracurricular activities and teacher conferences, and the cost of staff to supervise the children would take money away from more important educational programs.

After three years of studies on the educational impact of in-school lunch, including pilots where students wrote essays on their feelings about eating lunch in school, and the formation of another group in favor of single sessions (the “Working Mothers”), parents’ support for a single-session school day increased from 56% to 70%, while opposition from NPS administrators and staff remained constant at over 90%.

The lunch issue was resolved at an April 1969 School Committee meeting, so crowded with “orderly, but angry parents” that it had to be moved to a nearby school auditorium. After three hours of debate – most of it behind closed doors in an executive session while the crowd of parents waited outside – a compromise was reached. Elementary schools would have an opt-in, five-day-a-week, half-hour school lunch, paid for by those who chose it. Tuesdays and Thursdays would remain half days from 8:15AM to 12:30PM.

By 1974, lunch had become moot. NPS was busy installing ovens in its 23 elementary schools for meals that were “not much different from frozen dinners,” delivered by Stop and Shop. State and Federal mandates required a hot lunch be available for all public school children.

Parents were not the only group protesting in the 1960s. On October 9, 1964, about 200 students picketed Newton High School, chanting “Let Robin Back In.” Robin McNamara had been expelled for having “Beatle-style” long hair. Until 1967, NPS had a dress code to maintain “the educational atmosphere” and avoid “poor taste.”

Evolution of school politics

“The city’s major achievement, however, has come in the collaboration on educational matters of old Yankees and the thousands of recent middle-class Jewish arrivals, most of them from the city.” [Shrag]

Before 1966, School Committee meetings were rarely attended by members of the public, and votes were unanimous in support of the Administration’s requests. According to Haskell Freedman (member 1949 – 1965), the function of the School Committee was “not to interfere with the operations of [the] school system. In Newton, we let the school administration and their staff conduct the operations.” Newton school politics were “clean and closed.” When there was a vacancy on the School Committee, “we go out and get a good man to run and clear the way for him politically,” said Irene Thresher (member 1941-1950). Between 1945 and 1975, an incumbent lost only once. In 1949, James Cahill, an Irish-Catholic, “employed in industry; worked nights in a tavern,” was elected. History records it as an accident; voters mistook him for a prominent banker with the same name. He served one term.

Continuous Learning Program

This all changed in 1966, when Meadowbrook Junior High (now Brown Middle School) moved its entire student body into the Continuous Learning Program (CLP). CLP began in 1962 as an alternative that students could opt into. By 1965, half of Meadowbrook’s students were in CLP, and the School Committee voted to move the entire school into the program.

CLP students had a traditional sequence for math and foreign language. English, science, social studies, and electives were mixed in terms of age and ability, with an array of course offerings, including some student-suggested courses. The New York Times called Meadowbook A Junior High that is like a College: “Social studies for one Meadowbrook unit last winter included such offerings as Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, The Struggle for Men’s Minds, Advanced Economics, Colonial Period in American History, Communism, Vietnam War, Reform Movements in American History, Music of Protest and Propaganda, Elizabethan History, Public Speaking, Music and War, and Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire.”

Instead of letter grades, there were parent-teacher conferences and written reports. Students were responsible for their learning. Teachers were guides. Together, they wrote and signed a contract for tasks to be completed in each course (i.e., three books read and an essay written). Assessment was based on the teacher’s belief in the student’s potential rather than a class standard.

With the decision to move the entire school to CLP, “the handful of mothers who had been quietly protesting CL grew rapidly into an organization of irate parents called The Concerned Parents Committee.” (Alpert) They charged that CLP failed to teach students the skills needed to succeed in college and that, for unmotivated students, CLP amounted to continuous loafing. “About 125 anxious and angered parents” attended a School Committee meeting with a petition signed by 700 opposing the expansion of CLP and requesting that NPS allow open enrollment (the ability of students to transfer to one of the other four, traditional, Junior High Schools).

The School Committee stood by its decision. When the Concerned Parents Committee threatened to sue, School Committee Counsel and former member Haskell Freedman replied, “the final decision of the School Committee with regard to educational programs is not subject to judicial review.”

Rebuffed, the Concerned Parents Committee convinced one of their members, Alvin Mandell, to run for an open seat on the School Committee. He ran on a platform that called for voluntary participation in educational experiments, better relations between the School Committee and the City and community, more efficient school spending, and the single-session school day with in-school lunch and no free Tuesday and Thursday afternoons. He won handily and made enough noise about CLP that the State Department of Education became involved.

The State commissioned a study of the students from Meadowbrook in senior high school (Grades 10, 11, and 12). Results were presented at a special meeting requested by Mayor Basbas and Mandell in August of 1968. The study found that CLP students were behind in writing and math, but they caught up by their senior year. SAT scores were the same as those from other junior high schools. NPS administration contended that the type of achievements CLP fostered — self-discipline, responsibility, creativity — “could not be measured by standardized tests.” To appease the protesting parents, NPS agreed to give letter grades in math, foreign language, and all 9th-grade subjects. Public protest faded away.

A 1969 Harvard University study found that some students thrived in CLP, while others got away with “the least effort possible,” and that CLP “resulted in a decrease in achievement motivation among the males.” It concluded: “No learning situation will be ideal for all students. Whether ‘contracts,’ programmed instruction, individualized learning, or other modes of teaching are employed, the response of students will vary as a function of many individual differences, e.g., sex, I.Q., attitudes, parental concerns. Although these facts seem painfully obvious, a great deal of educational planning in the country at this time assumes that a new program will be equally beneficial to all students.”

First alternative high school in the U.S.

Newton also had the first alternative high school in America: The Murray Road Annex. A repurposed elementary school near Newton High School, Murray Road opened in 1967 with 115 students and 8 teachers, as an experiment in supervised, liberally structured “self-education”. Similar to Meadowbrook, students received written reports rather than grades and were involved in determining the school’s rules and curriculum. Unlike Meadowbrook, it was an opt-in high school. The Murray Road Annex closed in 1975 due to declining enrollment.

Next: Part 11: School Committee Politics and Asbestos in the New High School

Bibliography

Alpert, Richard M. Professionalism, Policy Innovation and Conflict: School Politics in Newton, Massachusetts. Cambridge, Harvard University, Department of Government Thesis, 1971.

Dow, Peter B. Schoolhouse Politics: Lessons from the Sputnik Era. Harvard University Press, 1991.

Hartman, Sylvia. “The Newton School Lunch Caper.” McCall’s, vol. XCVI, no. 12, 1969.

Kayakachoian, Gary. “Action in Newton.” Boston Globe [Boston], 7 February 1964. Accessed 6 January 2026.

Shrag, Peter. “Newton: Pipeline from Harvard.” Saturday Review, 16 January 1965, pp. 49-65.

Zelnicker, Dora, and Alfred Alschuler. “An Evaluation of the Motivational Impact of Individualized Instruction at Meadowbrook Junior High School.” Achievement Motivation Development Project, 1969, pp. 157-187. ERIC, https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED029139.pdf.